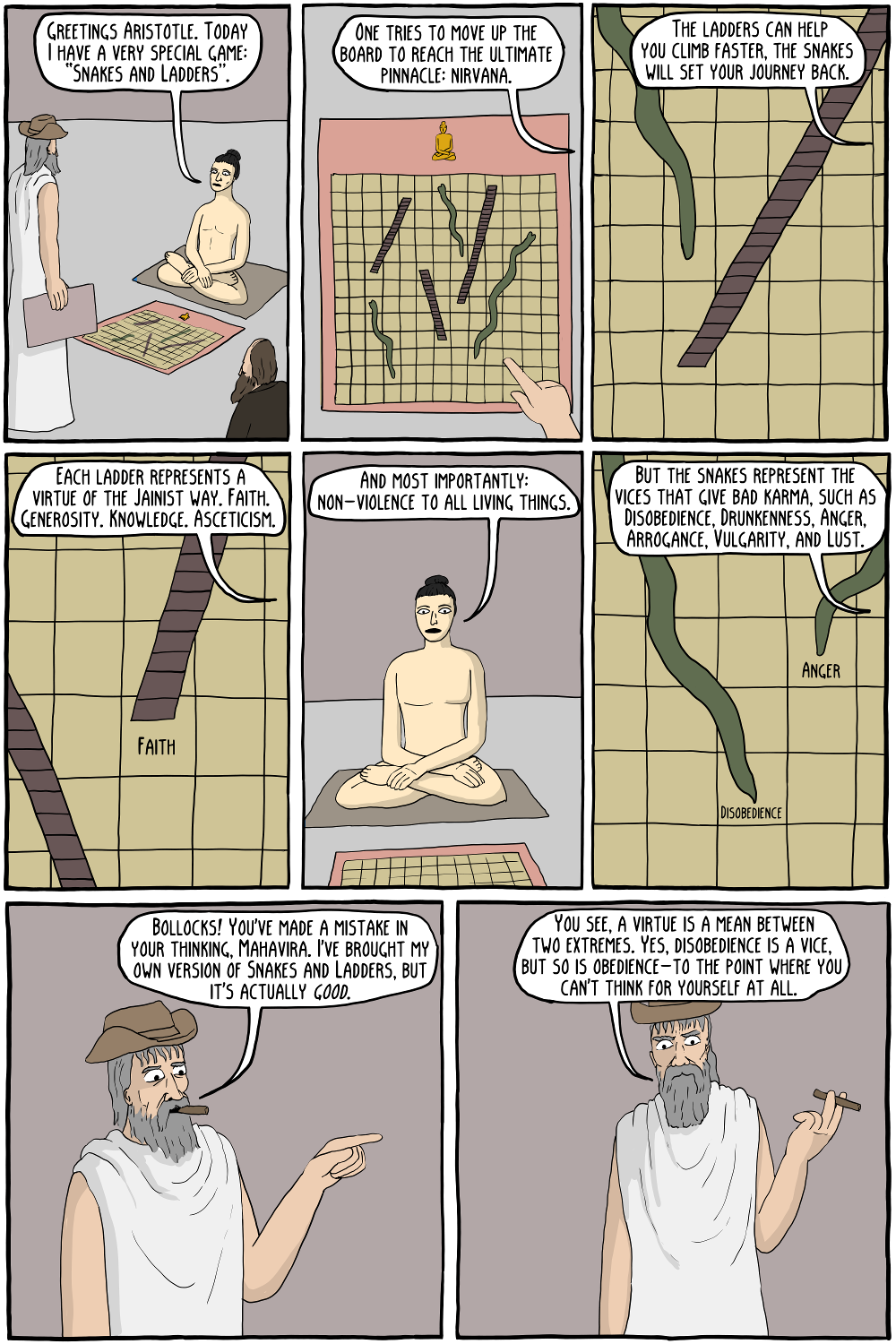

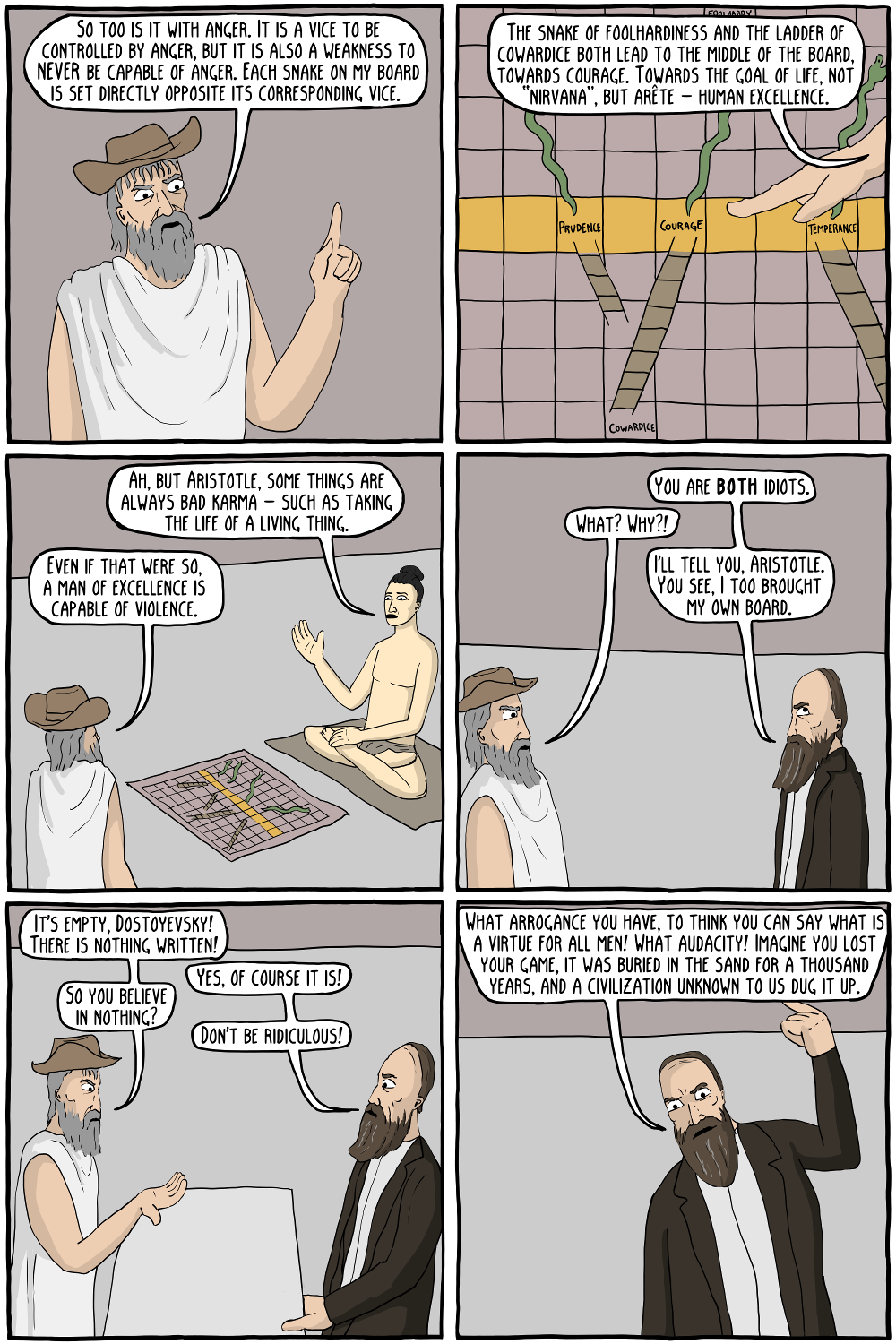

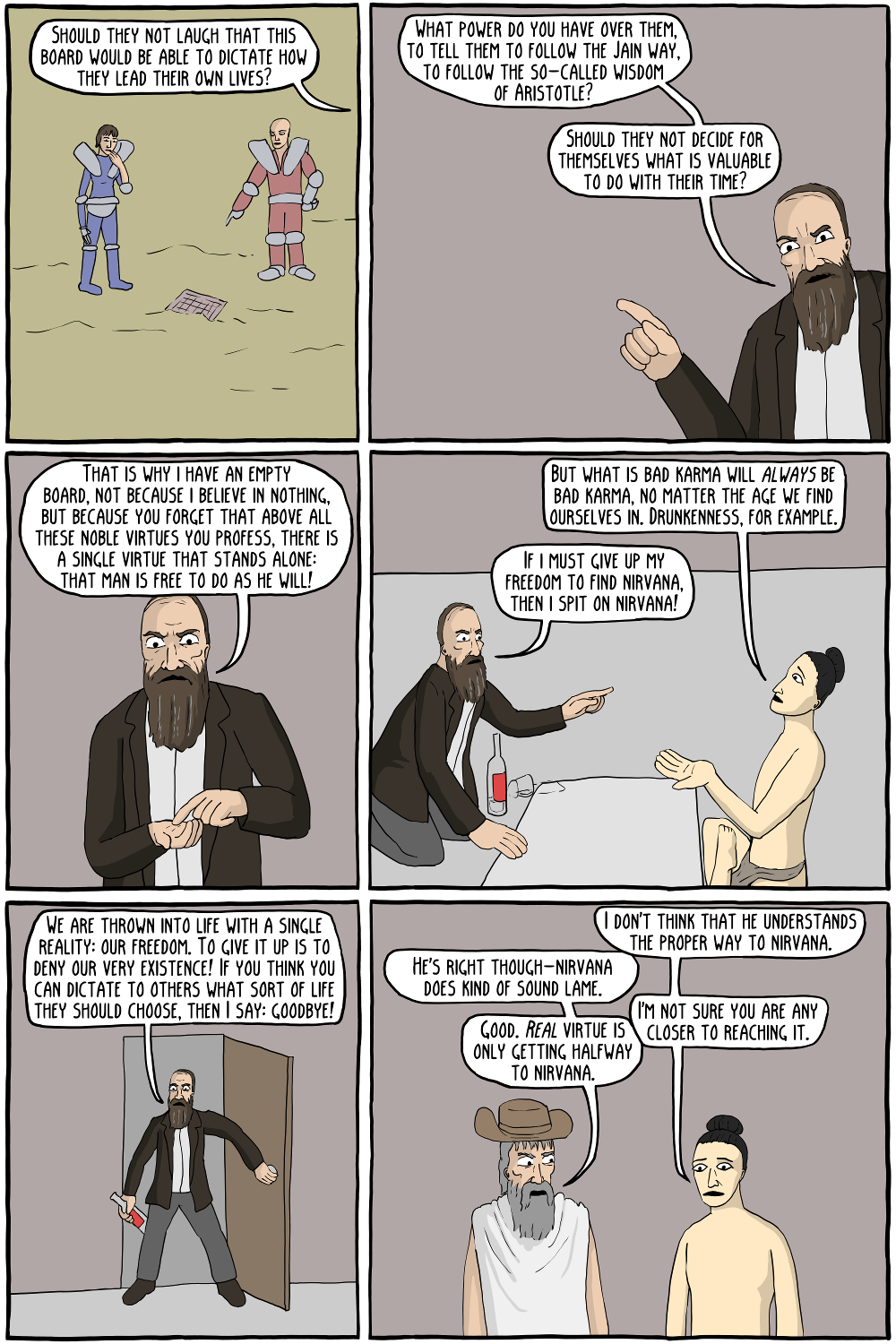

Snakes and Ladders (often known as Chutes and Ladders in the United States) was originally developed in India around the 2nd century BC. It was an educational game, used to teach the virtues of the Jainist and Hindu faiths. As in the comic, the ladders represented the virtues that would help you attain nirvana, and the snakes represented vices that would set you back. The game was played with dice, and the player was also supposed to reflect on how they didn't have control over how the pieces moved, which symbolized destiny. In Jainist philosophy, the most notable thing is complete non-violence. Killing any living thing is forbidden, and considered to impede the way to nirvana. Self-control and asceticism are also important parts of the religion, and it shares many common themes with Buddhism.

For Aristotle, the goal of life was to become an ideal person, and similar in some ways to India philosophies, the "good life" and the virtuous life coincided. However, for Aristotle, virtues were mostly understood to be a mean between two extremely, both of which strayed from what it meant to be an excellent human being. For example, "courage" is certainly a virtue, but it isn't just being able to face your fear - it is also being able to know when to fear. A man who had no fear at all would also fail to be an excellent human being, because they would take unnecessary risks. So courage isn't simply a positive virtue where the more you have the better, if you have too much you are "foolhardy", which is also bad. Coming to a balance between extremes allows a person to act justly, wisely, and effectively.

For Dostoyevsky, the idea that a single certain path could take humanity to happiness was a contradiction. In Notes From The Underground he attacks the ideas of people like Aristotle, as well as contemporary utilitarian thinkers, who believed that we could come to a final conclusion about what would render mankind happy; and if we did, then everyone would naturally enough follow that path towards their own happiness. Dostoyevsky says that there is one virtue that is above all others: the freedom to do as you please. He claims that even if we were to somehow figure out the exact way to make everyone as happy as possible, humanity would revolt against it just to exert their own freedom. In this sense, it is impossible for humans to be totally happy. This doesn't, however, mean that Dostoyevsky was some kind of moral relativist, believing that any life was just as good as any other. He certainly believed that we could make bad decisions about the kind of life to lead, and favored a certain kind of religious life above others. He just thought that a single, final solution was contradictory, because no one would do it if it was set in stone, with no room for freedom.

If you are interested more in the history of the game Snakes and Ladders, Extra Credits did a great video on how different cultures adopted the game, but changed the virtues and vices to suit their own ideals.

Permanent Link to this Comic: https://existentialcomics.com/comic/113

Support the comic on Patreon!