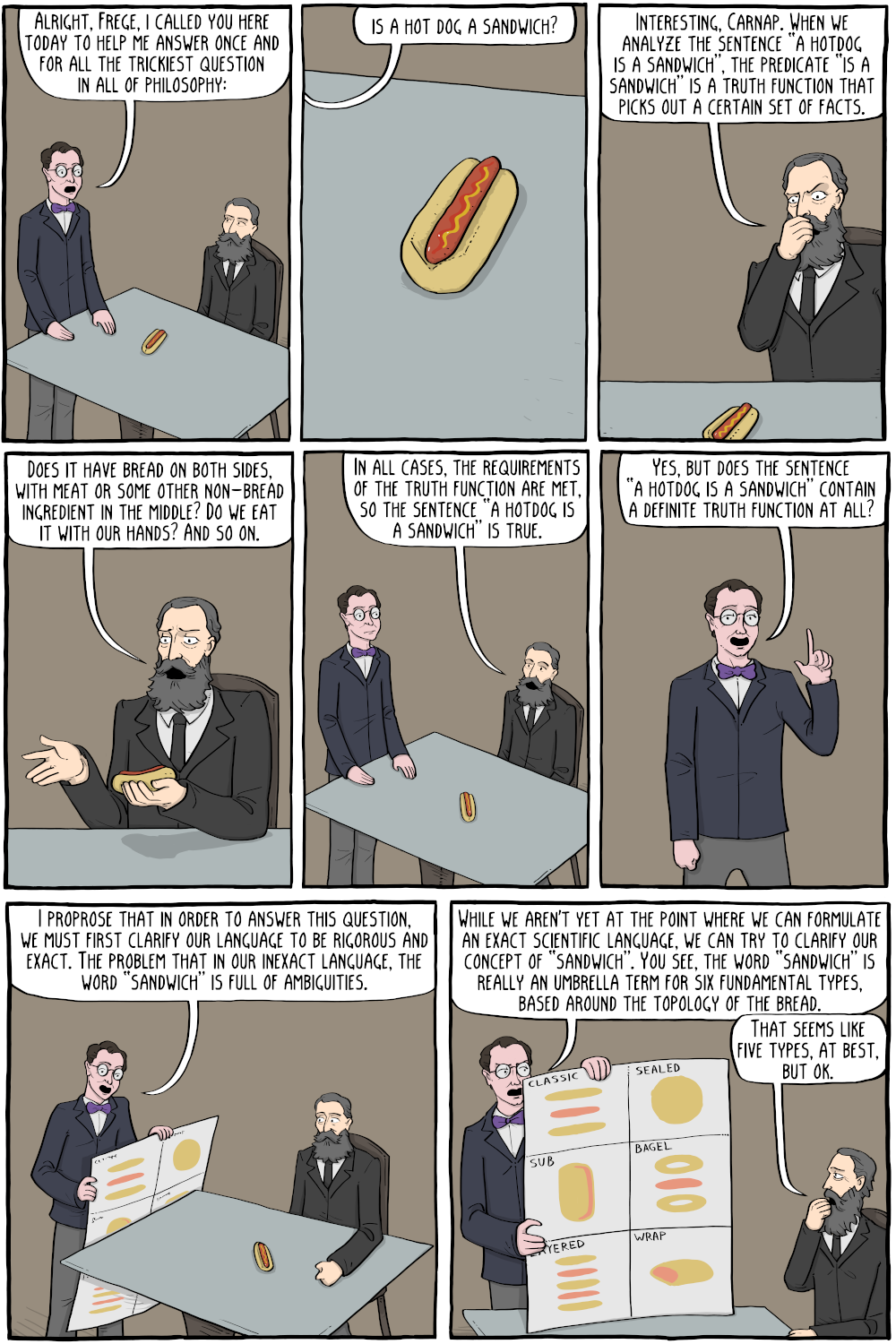

Frege was an early philosopher of language, who formulated a theory of semantics that largely had to do with how we form truth propositions about the world. His theories were enormously influential for people like Russel, Carnap, and even Wittgenstein early in his career. They all recognized that the languages we use are ambiguous, so making exact determinations was always difficult. Most of them were logicians and mathematicians, and wanted to render ordinary language as exact and precise as mathematical language, so we could go about doing empirical science with perfect clarity. Russell, Carnap, and others even vowed to create an exact scientific language (narrator: "they didn't create an exact scientific language").

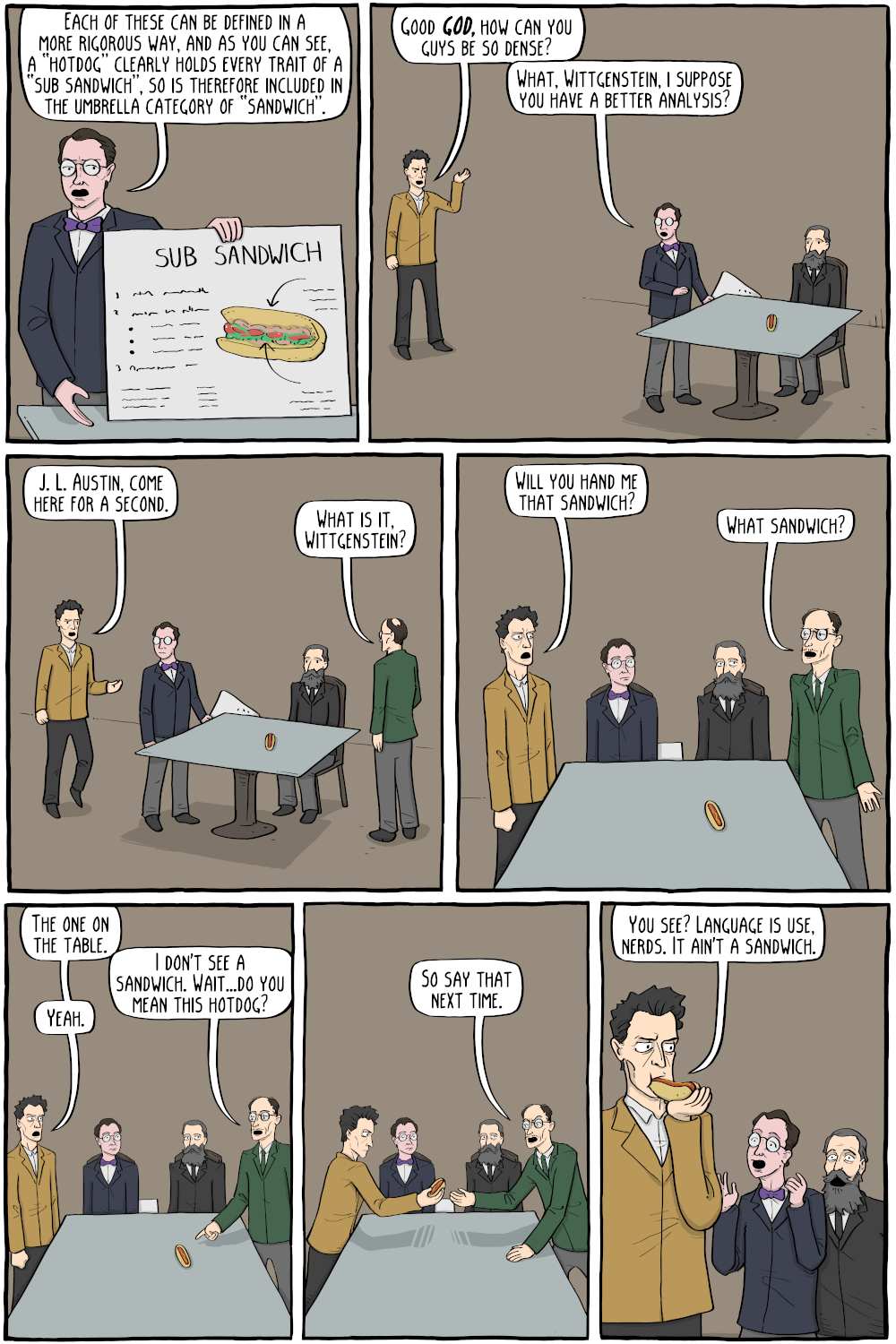

Later on, Wittgenstein and other philosophers such as J.L. Austin came to believe that a fundamental mistake was made about the nature of language itself. Language, they thought, doesn't pick out truth propositions about the world at all. Speech acts were fundamentally no different than other actions, and were merely used in social situations to bring about certain effects. For example, in asking for a sandwich to be passed across the table, we do not pick out a certain set of facts about the world, we only utter the words with the expectations that it will cause certain behavior in others. Learning what is and isn't a sandwich is more like learning the rules of a game than making declarations about what exists in the world, so for Wittgenstein, what is or isn't a sandwich depends only on the success or failure of the word "sandwich" in a social context, regardless of what actual physical properties a sandwich has in common with, say, a hotdog.

Permanent Link to this Comic: https://existentialcomics.com/comic/268

Support the comic on Patreon!